When Thivya’s mother returned from the hospital to find out her three young daughters had been arrested and detained during a raid, she voluntarily surrendered herself to Thai immigration police and joined her family at Bangkok’s international detention center (IDC). Two years went by before they were released on bail.

Thivya is among hundreds of refugees that are regularly detained by Thai immigration police in an effort to deter migration. While all types of undocumented migrants may be detained, refugees are a particularly vulnerable group because they often lack legal documents, social connections, and are unable to return home for fear of persecution.

Thailand has never signed the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and has no domestic framework that governs refugees and their rights. Refugees without visas from neighboring countries are regularly deported back, and those from further abroad may be detained indefinitely.

A largely unseen population is Thailand’s +8,000 urban refugees. They come from countries all over the world, including Pakistan, Syria, Iraq, China, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Somalia and are fleeing armed conflicts and persecution.

They live a precarious existence: Due to their constant fear of being arrested and detained they reduce movement within the city and hide in cramped living quarters.

Aamir, a 29 year old Palestinian refugee client describes the situation: “This issue could easily put us in jail. I try as much as possible to avoid being on the streets or going out regularly.”

Despite refugees’ efforts to remain unnoticed, Asylum Access Thailand (AAT) has witnessed a spike in the number of raids and arrests carried out by Thai immigration police in recent years, resulting in the detention of hundreds of refugees.

In response, AAT and six other organizations in Thailand prepared a joint UN submission that voices their concerns regarding the use of detention on refugees and calls on the Thai government to make immediate changes to its policies.

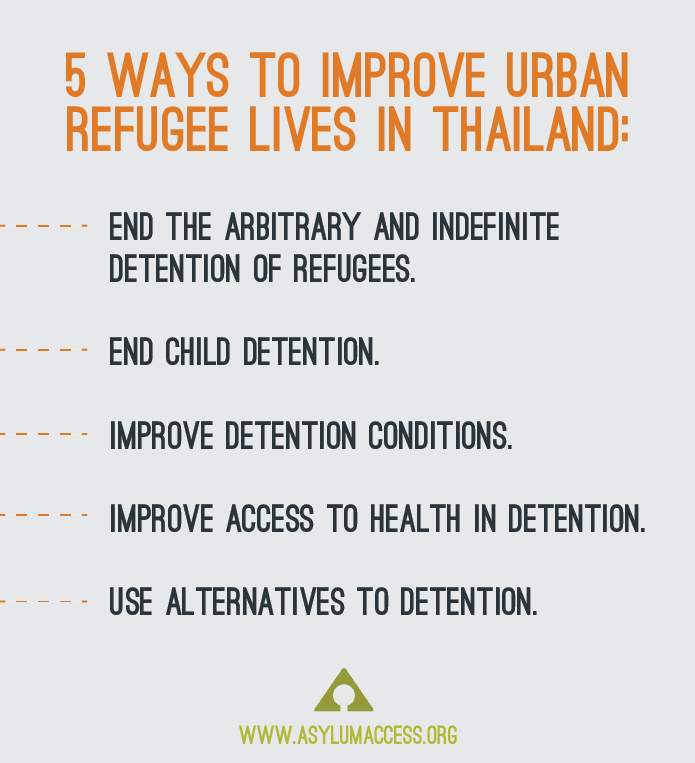

The road to improving Thailand’s perception and treatment of urban refugees is a difficult one to navigate, and shortcuts are practically non-existent. However, the following recommendations, implemented today, would vastly improve the lives of many refugees in detention, or facing the possibility of detention:

1. End the arbitrary and indefinite detention of refugees.

1. End the arbitrary and indefinite detention of refugees.

Refugees are frequently the targets of police raids, and are detained if they are unable to show a valid visa. This is true even if refugees have documentation from the UN Refugee Agency.

Refugees are only released from detention if they are resettled to a third country, granted bail, or agree to cover the return trip back to their country. Each of these options is rare and may take years to achieve.

Human Rights Watch’s recent report on detention in Thailand, ‘Two Years, No Moon,’ states that the average length of stay is 298 days (10 months), while the Jesuit Refugee Service has reported some refugees detained for 4-5 years

In the meantime, civil society organizations, including legal services providers, are unable to speak with at-risk populations held in IDCs.

Refugees in the asylum process should not be detained, and those detained should have access to legal assistance to make their case for asylum.

2. End child detention. Detention is particularly hard on children. While detained, they are unable to access education, proper nutrition or healthcare at key points in their lives, causing severe setbacks in their development. In Thivya’s case, she lost two years of her education while in the IDC, and that’s not counting the three years prior during which she lived in hiding.

If Thivya’s mother hadn’t surrendered herself, Thivya and her sisters would have been left to their own devices in the IDC. Refugee children are often detained and separated from their parents for periods longer than a year. They are held from a young age with unrelated adults, leaving them vulnerable to sexual abuse. They are forced to endure conditions that lead to stress, depression, fear, and alienation.

AAT and coalition organizations have called for the end of the detention of children by 2020 at the latest.

3. Improve detention conditions. Detention centers are desperately overcrowded and unsanitary, sometimes holding over 100 people in one cell. In 2013, the World Health Organization found there to be approximately 880 to 1,000 people detained in the Bangkok Immigration Detention Center, with approximately 3 square meters per person. Entire families may be separated and men are often placed in jails or holding cells if there is no space in the IDC.

In the Human Rights Watch report, ‘Two Years, No Moon,’ interviewees described appalling sanitation conditions, with limited water, filthy wash areas, tainted food, and insufficient numbers of toilets. The cells are infested with insects and detainees often suffer from acute skin conditions.

4. Improve access to health in detention. Refugees are held in overcrowded facilities regardless of their age or health. Due to limited budgets, adequate healthcare does not exist in detention, and is nonetheless extremely difficult to access.

Detention has been shown to re-traumatize refugees; the British Journal of Psychology, cited by Human Rights Watch, found in 2009 that detained refugees experienced high instances of mental health difficulties including ‘anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicidal thoughts’.

5. Use alternatives to detention. Detention is not the solution to control irregular migration. Other countries have found effective, and affordable, alternatives to detention.

The Philippines implemented a successful recognizance release scheme where refugees, asylum seekers and migrants receive appropriate documentation and are released on the condition that they periodically check in with the department of justice. Children are always released following referral to the department of Social Welfare and Development who provide assessment by a social worker, shelter and healthcare.

In the United States, alternative approaches to detention have been found to lower financial and human costs, and result in higher wellbeing and better attendance of refugees to the legal proceedings for their case.

Such schemes offer a promising vision for the refugees currently detained in Thailand but would first require Thailand’s recognition of refugees.

Though the Thai government responded favorably to five of the recommendations following the joint UN submission, changes have yet to be seen on the ground. AAT and coalition partners are continuing advocacy efforts that would ensure sustainable solutions that also do not interfere with the wellbeing of Thailand’s urban refugees.

Written by Creative Lead Sandra ten Zijthoff